Sn-syo-tyen (Chinese,

shan shò chím), "personally counting divination," is a kind of

fortune telling practiced with dominoes. The inquirer shuffles a set of dominoes

face down and arranges them side by side in a line. He then turns them face up,

preserving the arrangement, and selects as many of the combinations referred to

on pages 523-524, as can be formed by contiguous pieces. The sum of the numbers

there given, in connection with the combinations thus formed is noted, and the

operation twice repeated. The three results are added together, and if their sum

amounts to 32, the number of the domino pieces, the augury is very good; more or

less being estimated proportionally good or indifferent.

Sn-syo-tyen (Chinese,

shan shò chím), "personally counting divination," is a kind of

fortune telling practiced with dominoes. The inquirer shuffles a set of dominoes

face down and arranges them side by side in a line. He then turns them face up,

preserving the arrangement, and selects as many of the combinations referred to

on pages 523-524, as can be formed by contiguous pieces. The sum of the numbers

there given, in connection with the combinations thus formed is noted, and the

operation twice repeated. The three results are added together, and if their sum

amounts to 32, the number of the domino pieces, the augury is very good; more or

less being estimated proportionally good or indifferent.

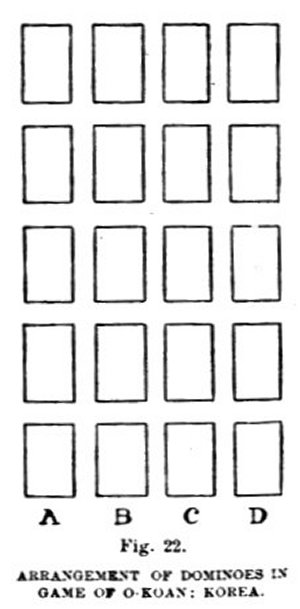

Another popular method of divination with dominoes is called o-koan (Chinese, 'ng kwán), "5 gateways". An entire set of 8 dominoes is reversed and shuffled and 20 pieces are then arranged face down in 5 rows of 4 pieces each (Figure 22). The player then turns these pieces face up and commencing at the bottom row endeavors to form combinations of 3 pieces each, han-hpai such as have been described under ho-hpai In addition to the han-hpai already enumerated, page 523-524, the following additional ones are permitted in o-koan.

Three pieces upon which 3 of the spots are alike and the sum of the other 3 [Page 527] spots is equal to 5, called sam-tong-tan-o-tyem (Chinese sám t'ong tan 'ng tim,) "three alike and only five spots," and 3 pieces upon which 3 of the spots are alike and the sum of the other 3 spots is equal to or more than 14, called sam-tong-sip-sà-tyem (Chinese sám t'ung shap sz' tim,) "three alike and fourteen spots."

In forming these combinations, 3 contiguous, pieces in a row may be taken, or 1 or 2 pieces at one end of a row may be used in combination with 2 pieces or 1 piece at the other end, the pieces thus taken being always placed on the inner side. Thus the piece A may be mated with C D to form a combination A C D, or B A may be mated with D to form a combination A B D. The combinations thus formed are removed and placed in a line face up above the 5 rows, the one found nearest the bottom being placed to the left and successive ones to the right of the line thus started. When no more combinations can be discovered, 5 pieces are drawn from the unused pile of 12 pieces which have been left with their faces down, and one of them placed face down to the right of each of the 5 rows. These 5 pieces are then turned face up, and an attempt made to form combinations of threes with their aid. The results are successively placed to the right of the line at the top and this process is continued until the 12 extra pieces are exhausted. When this happens, 5 pieces are withdrawn from the left of the top line and added in succession to right of the 5 rows. If, by chance, but 4 or a less number of rows remain, only a corresponding number of pieces are drawn. This process is continued over and over until all the pieces are combined in sets of threes in a long row at the top, or the top row is exhausted and a block ensues, determining success or failure.

The name of the game is said to have been taken from a well-known episode in the life of Koan Ou1 (Chinese, Kwàn Ü), the [Page 528] celebrated Chinese general, now universally worshiped in China as the God of War, and one of the heroes of the famous historical romance, the Sám Kwok chí, or "Annals of Three States." In escaping from Ts'ao Ts'ao,2 it is recorded that he killed six generals at "five frontier passes," o-koan (Chinese 'ng kwán). The vicissitudes of his life at this time are typified in the varying fortunes of the game, which at one moment approaches a successful termination, only for the player to be unexpectedly set back to overcome its obstacles anew. The conquest of the "five koan," which Koan Ou achieved, finds it analogue in the 5 rows of the dominoes which the player struggles to overcome. Many educated people play this game every morning, and scholars who have nothing to do play it all day long, finding intellectual pastime in its elusive permutations.

Notes:

1. Kwan Yü (Kwàn Ü) AD 219. Designated Kwan Chwáng Miú

and deified as Kwan Ti or Wu Ti, the God of War. A native of Kiai Chow, in

Shan-si, who rose to celebrity toward the close of the second century

through his alliance with Liu Pei and Chang Fei in the struggles which

ushered in the period of the Three Kingdoms. He is reputed to have been, in

early life, a seller of bean-curd, but to have subsequently applied himself

to study until, in AD 184, he casually encountered Liu Pei at a time when

the latter was about to take up arms in defense of the House of Han against

the rebellion of the Yellow Turbans. He joined Liu Pei and his confederate,

Chang Fei, in a solemn oath, which was sworn in a peach-orchard belonging to

the latter, that they would fight henceforth side by side and live and die

together. The fidelity of Kwan Yu to his adopted leaders remained unshaken

during a long series of years in spite of many trials; and similarly his

attachment to Chang Fei continued throughout his life. At an early period of

his career he was created a t'ing how (baron) by the regent Ts'ao Ts'ao,

with the title of Hán shu t'ing hau. … His martial powers shone

conspicuously in many campaigns which were waged by Liu Pei before his

throne as sovereign of Shu became assured, but he fell a victim at last to

the superior force and strategy of Sun K'üan, who took him prisoner and

caused him to be beheaded. Long celebrated as one of the most renowned among China's

heroes, he was at length canonized by the superstitious Hwei T'sung, of

the Sung dynasty, early in the Twelfth century, with the title Chung hwui

Kung. In 1128 he received the still higher title of Chwàng miú wu ngàn wàng,

and after many subsequent alterations and additions be was at length raised

in 1594 by Ming Wan Li to the rank of Ti, or God, since which date, and

especially since the accession of the Manchow dynasty, his worship as the

God of War has been firmly established. (Chinese Reader's Manual, No.

297.)

2. Ts'ao Ts'ao A D 220. Chinese Readers Manual, No. 768.

Last update January 31, 2010